Poem of Return by Jofre Rocha Analysis: Questions and Answers

Introduction to “Poem of Return” by Jofre Rocha: Questions and Answers – Analysis

“Poem of Return” by Jofre Rocha stands as a poignant reflection on exile, return, and the enduring scars of conflict. This analysis explores the depth of Rocha’s work through a series of questions and answers, delving into the significant elements of diction, imagery, and tone that shape the poem’s profound messages. Each question aims to unravel the layered meanings and emotions embedded in the text, providing insights into how the poem communicates the complex realities of those who stayed behind during times of upheaval, as well as the personal turmoil of the returning speaker. This approach not only enhances understanding of the poem’s literary qualities but also offers a broader perspective on its social and historical contexts, revealing why Rocha’s voice remains essential in discussions of resistance and remembrance in literature.

Poem Overview

“Poem of Return” by Jofre Rocha is a poignant reflection on the feelings of displacement and longing associated with exile. Rocha’s choice of imagery vividly conveys the raw emotions of returning to a homeland marked by conflict and loss. Instead of conventional welcomes like flowers, he seeks elements that bear witness to his homeland’s hardships—dews, dawn’s tears, and the pervasive hunger for love and understanding that characterizes his poetic voice.

About the Poet: Jofre Rocha

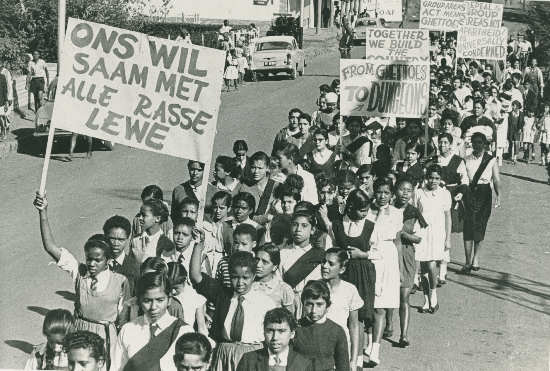

Jofre Rocha, whose birth name is Roberto Antonio Victor Francisco de Almeida, was born in 1941 in Caxicane, Angola. He adopted the pseudonym ‘Jofre Rocha’ as a ‘war name’ during Angola’s struggle for independence. Rocha’s early life in rural Angola was deeply influenced by political unrest and guerrilla warfare, prompting his family’s move to Luanda where he became an active political activist. His activism led to his imprisonment between 1961 and 1968, a period during which he also pursued his academic studies.

Post-Independence Career

After Angola gained independence in 1975, Rocha continued his involvement in politics as a member of the ruling MPLA party. He held various government positions and significantly contributed to the cultural landscape of Angola as a founding member of the Union of Angolan Writers. Rocha’s extensive body of work includes over twenty-two works in seventy-three publications, highlighting his prolific contributions to literature and social thought.

Literary Themes and Diction

The diction in “Poem of Return” is carefully chosen to reflect deep-seated emotional and physical landscapes. Terms such as “Land of Exile”, “dews”, and “drama” convey both the physical reality and the emotional weight of exile and return. The phrase “immense hunger for love” and the “plaint of tumid sexes” illustrate the complex interplay of desire, conflict, and the human condition that Rocha often explores in his poetry.

Rocha’s poetry is not just an expression of personal sentiment but a broader commentary on the socio-political conditions of Angola during a tumultuous period. His works serve as a bridge between personal experiences and national history, providing a powerful voice for those who have suffered displacement and longing.

Summary and Analysis of “Poem of Return”

“Poem of Return” by Jofre Rocha is an introspective piece that explores the complex emotions tied to the poet’s anticipated return to his homeland after a period of exile. The poem is structured around the speaker’s reflections on his displacement and the struggles endured by his compatriots in his absence. It captures the profound sense of loss, missed opportunities, and the alienation felt in a “land of exile and silence,” suggesting dissatisfaction and unhappiness in the host country.

Reflections on Exile and Return

The speaker contemplates his return with mixed feelings, addressing the contrast between his survival in exile and the sacrifices made by those who stayed behind. He explicitly states that he does not view himself as a hero, underscoring a sense of guilt for having survived while others suffered or died under oppressive conditions. This sentiment is expressed through his refusal of traditional symbols of welcome like flowers, instead requesting tokens that symbolize the true cost of the struggle endured by his people—tears, dews of dawn, and the intense yearning for connection and love lost during the years of conflict.

Themes of Guilt and Heroism

The poem delves into themes of guilt and the nuanced definition of heroism. Rocha challenges conventional notions of heroism, redirecting admiration towards those who remained in the homeland, fighting against colonial and oppressive forces. This perspective is a poignant reflection on the personal and collective sacrifices that define political and social struggles.

Cultural and Political Commentary

Through his vivid imagery and emotional depth, Rocha also critiques the lasting impacts of colonialism, war, and exile on personal and national identities. The poem is a powerful lament for the “lost opportunities, mourning, and sadness” brought about by these forces, offering a voice to the often silent suffering and resilience of the oppressed.

Jofre Rocha’s “Poem of Return” not only narrates a personal journey but also serves as a broader commentary on the socio-political upheavals experienced by Angola. It encapsulates the complex emotions of returning to a place that has endured much suffering and transformation, making it a significant piece in the study of post-colonial literature and the human condition.

Line-by-Line Analysis from “Poem of Return”

Stanza 1

Line 1-2: Refusal of Flowers

In the opening lines, the speaker states, “When I return from the land of exile and silence, do not bring me flowers.” This explicit rejection of flowers, traditional symbols of celebration or a hero’s welcome, sets a somber tone for the poem. The speaker does not view his return as a triumphant event but rather as a reflective and profound acknowledgment of ongoing struggles.

Line 3-4: True Heroes

The speaker deepens the narrative by emphasizing respect for those who stayed behind and faced the harsh realities of conflict. He shifts the honor to those who bear the scars of war, stating, “Bring me rather all the dews, tears of dawns which witnessed dramas.” This line elevates the survivors and fighters as the true heroes, focusing on their resilience and sacrifices rather than his own journey back.

Broader Implications

These lines underscore a profound sense of solidarity and reverence for his fellow countrymen and women who endured suffering and fought against the oppressors. The speaker’s return is framed not as a personal triumph but as a humble reintegration into a community that has endured much pain and loss. Through this stanza, Rocha articulates a narrative that challenges conventional notions of heroism, instead highlighting the collective struggle and the emotional and physical toll it exacts on those involved.

Stanza 2

Line-by-Line Analysis of Stanza Two from “Poem of Return”

Update on Home

In this stanza, the speaker seeks an update on the events that transpired during his absence. He expresses a desire to reconnect with the experiences of those who remained, underlining his need to understand and empathize with their struggles.

Line 5-6: Dramas Witnessed

The speaker asks to be brought “all the dews, tears of dawns which witnessed dramas”. This metaphorical request emphasizes his desire to absorb the raw emotions and significant events that unfolded—reflecting the intensity and the impact of the conflicts endured by his community.

Line 7-8: Shared Pains

Continuing from the previous thought, he seeks a deeper emotional connection by experiencing the collective pain, “Bring me the immense hunger for love and the plaint of tumid sexes in star-studded night.” These lines convey his need to feel the pains and the deep-seated yearnings that his people suffered, drawing him closer to the shared human experience of his community.

Broader Implications

These lines showcase the speaker’s profound need to empathize with and understand the emotional and physical toll on those who stayed behind. By immersing himself in their experiences and suffering, he seeks not only knowledge but also emotional solidarity with the ongoing struggles of his homeland. This stanza highlights his transition from an individual returning from exile to a member of a community bound by shared pain and resilience.

Stanza 3

Focus on Fallen Heroes

In this stanza, the speaker shifts focus to commemorate those who fought and died in the war of liberation, particularly those who did not live to see the day of independence.

Line 9-10: Tribute to the Fallen

The speaker repeats his request from the first stanza, emphasizing, “When I return from the land of exile and silence, no, do not bring me flowers …” This repetition serves as a somber reminder that traditional symbols of welcome or celebration are inappropriate given the sacrifices made.

Line 11-14: Honoring Their Last Wishes

He asks to be brought “only, just this—the last wish of heroes fallen at day-break”. The phrase “heroes fallen at day-break” poignantly symbolizes those who died at the beginning of a new era, just as independence dawned. The mention of “a wingless stone in hand” suggests unfulfilled potential and unfinished battles, while “a thread of anger snaking from their eyes” implies lingering resentment and unresolved struggles.

Broader Implications

This stanza serves as a tribute to the martyrs of the liberation struggle, highlighting the profound loss and the unfinished nature of their fight for freedom. By focusing on these fallen heroes, the speaker underscores the deep scars left by the war and the ongoing need for remembrance and justice. The imagery used enriches the narrative, adding layers of meaning to the sacrifices that shaped the nation’s history. This stanza not only reflects a personal journey of return but also a collective memory of loss and the enduring spirit of resistance.

The structure of the Poem

Form and Structure of “Poem of Return”

Jofre Rocha’s “Poem of Return” employs a form that is evocative of contemporary poetry while deviating from classical structures such as the sonnet. Here are the key features of the poem’s form and structure:

Non-Sonnet Structure

Despite consisting of 14 lines, the poem does not conform to the traditional sonnet structure, which typically features a specific rhyme scheme and a volta (turn of thought). Rocha’s choice emphasizes the modern and free-flowing nature of his poetic expression.

Enjambment

The poem makes extensive use of enjambment, where one line flows into the next without terminal punctuation, contributing to a more conversational and urgent tone. This can be seen in transitions between lines such as 5-6 and 7-8, where the continuation of thought across lines mirrors the ongoing and unresolved issues addressed in the poem.

Refrain

The repeated phrase “do not bring me flowers” acts as a refrain throughout the poem, enhancing its musical quality and reinforcing the central theme of rejecting traditional celebratory gestures in favor of a more profound and somber reflection.

Free Verse

The poem is written in free verse, typical of contemporary poetry, which allows for greater flexibility in expression and structure. This format supports the poem’s thematic exploration of freedom and constraint, mirroring the poet’s own experiences with political censorship.

Unequal Stanza Length

The division into three stanzas of unequal length reflects the varying intensities and focus of the thematic elements discussed in each section. Each stanza introduces a different perspective or element of the speaker’s anticipated return, from the personal to the collective, from the emotional to the commemorative.

Use of a Pseudonym

The use of a pseudonym by the poet, necessitated by censorship, adds another layer of complexity to the poem, highlighting the risks and constraints under which the poet operated. This background enriches the reader’s understanding of the poem as not just a personal narrative but also a political statement.

This form and structure analysis reveals how Rocha’s techniques contribute to the depth and impact of his poetry, reflecting both personal experiences and broader socio-political themes.

Deep Analysis of “Poem of Return” by Jofre Rocha

Stanza One: Exile and Isolation

Line 1: The phrase “When I return from the land of exile and silence” highlights the speaker’s certainty and inevitable return to his homeland, despite currently being in exile. The term “land of exile” suggests a place of forced retreat, while “silence” underscores the isolation and lack of communication with loved ones, amplifying the emotional pain of his separation.

Line 2: “do not bring me flowers.” The use of the imperative “do not” reveals a commanding tone. The speaker rejects traditional celebratory gestures, such as flowers, which symbolize happiness and welcome. This rejection reflects his feelings of guilt for having left his countrymen to endure the struggles alone, and his view that his return does not warrant celebration due to the ongoing suffering of others.

Stanza Two: Yearning for Connection and Witness to Suffering

Lines 3-4: “Bring me rather all the dews, tears of dawns which witnessed dramas.” This command, repeated for emphasis, expresses a desire to be connected to the intense experiences—both natural and human—that persisted in his absence. The personification of dawn as a “weeping witness” and the harsh alliteration of “d” sounds emphasize the severity and sadness of the events witnessed.

Lines 5-6: “Bring me the immense hunger for love and the plaint of tumid sexes in star-studded night.” Here, the speaker underscores the deep human need for intimacy and connection that he missed. The words “immense” and “plaint of tumid sexes” highlight the physical and emotional longing exacerbated by separation due to exile.

Lines 7-8: “Bring me the long night of sleeplessness with mothers mourning, their arms bereft of sons.” These lines depict the endless sorrow of mothers who lost their sons to conflict or exile. The prolonged “night of sleeplessness” symbolizes the ongoing distress and worry over the safety and fate of loved ones.

Stanza Three: Homage to the Fallen

Lines 9-10: The repetition of the first line of the poem emphasizes that the speaker’s return should not be seen as a celebratory event. The forceful “no, do not bring me flowers”_ underlines his insistence on not being treated as a hero, reflecting his ongoing internal conflict and sense of guilt.

Line 11: “Bring me only, just this” The redundancy in “only, just this” stresses the singularity and importance of his request, focusing on the essence of what he feels is necessary for his return.

Line 12: “the last wish of heroes fallen at day-break” suggests that the fallen heroes’ last desires were for the dawn of a new era of change, which they did not live to see. This metaphor of “day-break” as both a literal and symbolic new beginning underlines the tragic timing of their deaths at the cusp of change.

Lines 13-14: “with a wingless stone in hand and a thread of anger snaking from their eyes.” The “wingless stone” symbolizes the unfulfilled potential and actions of those who died without seeing their efforts come to fruition. The imagery of “anger snaking from their eyes” conveys a deep-seated resentment and the poisonous legacy of colonial oppression that continues to influence the living.

Overall, Jofre Rocha’s “Poem of Return” is a complex reflection on exile, loss, and the burdens of those who survive. The poem is a call to remember and honor the true costs of freedom and the sacrifices of those who fought for it, urging a recognition that transcends conventional celebratory gestures.

The Tone of the Poem

The tone of Jofre Rocha’s “Poem of Return” is complex and evolves throughout the poem, reflecting a spectrum of emotions connected to the speaker’s anticipated return from exile. Here are the key tones identified:

Regret and Sadness

The poem opens with a tone of regret and sadness, indicated by the speaker’s rejection of traditional celebratory symbols like flowers. This mood is established through references to the “land of exile and silence,” emphasizing the speaker’s feelings of alienation and estrangement. The melancholic tone is underscored by the longing for a connection with the harsh realities left behind, rather than superficial celebrations.

Nostalgic and Earnest

As the poem progresses, there is a nostalgic tone when the speaker reflects on the experiences and sacrifices of those who remained in the homeland. This nostalgia is paired with an earnest desire to reconnect with the lost time and to understand the “tears of dawns which witnessed dramas.” The speaker’s requests for tokens of endured suffering rather than flowers convey a deep earnestness to embrace the full emotional weight of what was experienced in his absence.

Humble and Militant

The tone also becomes humble as the speaker acknowledges that he does not view himself as a hero and dismisses any heroic welcome. He expresses a clear preference for solidarity with those who truly suffered and fought, which transitions into a more militant tone towards the end of the poem. The description of “a thread of anger snaking from their eyes” signifies a buildup of anger and a call to remember the ongoing struggles and the sacrifices made by the liberation fighters.

Anger

The final lines of the poem crescendo into a tone of anger, encapsulated by the vivid imagery of “anger snaking from their eyes.” This anger is directed towards the injustices endured and the ongoing fight against oppression that the speaker connects with even in his absence. It suggests a rallying cry for remembrance and justice, channeling the collective resentment against the colonists and oppressors.

Overall, the poem’s tone shifts from personal grief and alienation to a collective call to action, intertwining the speaker’s personal journey with the broader political and social struggles of his homeland.

The mood of the Poem

The mood of Jofre Rocha’s “Poem of Return” is predominantly pensive, characterized by deep reflection on serious and poignant themes. The speaker’s contemplation of his return from exile is filled with introspection about the implications of his absence and the consequences it had on those who remained to face oppression. This mood is conveyed through the imagery of suffering and the sacrifices made by others, which the speaker wishes to acknowledge and honor instead of receiving celebratory gestures.

The pensive mood is also evident in the speaker’s rejection of flowers, a symbol typically associated with joyous occasions. Instead, he requests elements that represent the true emotional and historical weight of the struggles faced by his countrymen—such as the “tears of dawns” and the “immense hunger for love.” These requests reflect his serious engagement with the themes of loss, sacrifice, and the ongoing fight for justice, emphasizing a mood that is reflective rather than celebratory.

Overall, the mood of the poem invites the reader to engage with the complex emotions and historical realities of returning from exile, fostering a reflective and somber atmosphere that resonates with the speaker’s earnest desire to reconnect with the painful truths of his homeland’s past and present struggles.

Questions and Answers

Essay Question Examples and Guidance

Question 1:

In the poem “Poem of Return,” the speaker seems to believe that those who stayed behind during the exile suffered greatly. With reference to diction, tone, and imagery, discuss to what extent you agree with the above statement. Your response should be in the form of a well-constructed essay of 250-300 words.

Guidance for Answer:

In “Poem of Return,” the speaker uses somber and reflective diction, a melancholic and sometimes militant tone, and vivid imagery to convey the suffering of those who stayed behind. Phrases like “tears of dawns which witnessed dramas” and “mothers mourning, their arms bereft of sons” paint a picture of a community in distress. Discuss how the speaker’s choice of words emphasizes the emotional and physical toll on those who were not in exile. Analyze how the tone shifts from sadness to anger, reflecting a buildup of collective suffering and resilience against oppression. Consider the imagery of the “thread of anger snaking from their eyes,” which symbolizes the deep-seated resentment and ongoing struggle of his people.

Question 2:

Examine the use of symbolism in Jofre Rocha’s “Poem of Return.” How do symbols like flowers and stones contribute to the poem’s overall message about exile and return?

Guidance for Answer:

In the poem, flowers symbolize traditional welcomes and celebrations, which the speaker rejects, indicating that his return is not a joyous occasion but a reminder of unresolved strife and loss. The “wingless stone” represents unfulfilled potential and the burdens of those who fought for freedom but did not live to see the results. Discuss how these symbols contrast with each other and contribute to the poem’s themes of sacrifice and the complex emotions associated with returning from exile.

Question 3:

Discuss the role of nature imagery in conveying the themes of “Poem of Return.” What does the depiction of elements like dawn and night suggest about the speaker’s perception of his homeland and exile?

Guidance for Answer:

Nature imagery in the poem serves as a powerful conduit for expressing the emotional landscape of the speaker’s experiences. Dawn is personified as a witness to tragedy, suggesting the beginning of suffering and the continuous cycle of pain experienced by those at home. The “long night of sleeplessness” represents the enduring anxiety and sorrow of a nation under duress. Analyze how these natural elements enhance the emotional depth of the poem and reflect the speaker’s conflicted feelings about his return and the ongoing struggles of his people.

These questions encourage a deep analysis of the poem’s literary elements, inviting students to explore how Rocha uses language and symbolism to convey complex themes related to exile, return, and the human condition.

Short Questions and Answers

1. Why does the speaker not want flowers upon his return?

The speaker rejects flowers because they represent superficial gestures of welcome or celebration, which he feels are inappropriate given the suffering and struggles faced by those who remained in his homeland. He does not view himself as a hero deserving of accolades, emphasizing his guilt for having left others to fight.

2. What does the speaker want instead of flowers? Why?

Instead of flowers, the speaker requests symbols of suffering and emotional depth, such as tears, hunger, intimacy, mourning, and sleeplessness. He seeks recognition of the hardships endured rather than a celebratory welcome, highlighting the gravity of the ongoing struggles.

3. Comment on the description of the speaker’s “host country” as the “land of exile and silence”.

The terms “exile” and “silence” suggest not only physical displacement but also emotional and communicative isolation. The speaker may have felt linguistically and culturally alienated, adding layers of solitude and sadness to his experience of exile.

4. Identify and comment on the effectiveness of the figure of speech in “tears of dawns”.

The personification of “dawn” weeping (“tears of dawns”) is an effective use of personification, suggesting that even nature mourns the sorrows and tragedies experienced by the speaker’s homeland. This figure of speech deepens the emotional resonance of the poem, emphasizing the pervasive impact of the atrocities.

5. Why are the mothers “bereft of sons” (line 8)?

The phrase “bereft of sons” highlights the harsh realities of political strife where many young men were either imprisoned, killed, or forced into exile. This loss deeply affected their mothers, leaving them without their children and contributing to the poem’s overall mood of mourning and loss.

6. How does the imagery of “a wingless stone in hand” contribute to the poem’s message?

The imagery of “a wingless stone in hand” symbolizes the unfulfilled potential and the incomplete actions of those who died in the struggle. It suggests that these individuals were ready to fight but did not have the chance to see the outcomes of their efforts, reflecting on the premature loss of life and opportunity.

7. Analyze the use of the word ‘snaking’ in the context of the poem.

The word “snaking” evokes a sense of something hidden, dangerous, and slowly spreading. It effectively conveys the deep, underlying anger and resentment that grows among the oppressed, suggesting a pervasive and lingering bitterness that continues to affect the community.

8. Discuss the significance of the repeated command ‘do not bring me flowers’ throughout the poem.

The repeated command “do not bring me flowers” serves as a refrain that underscores the poem’s somber tone. It rejects traditional symbols of celebration to focus attention on the harsh realities of the speaker’s homeland. This repetition is a powerful rhetorical device that reinforces the speaker’s desire for recognition of suffering over superficial gestures of welcome.

9. What does the description of ‘the long night of sleeplessness’ suggest about the emotional state of the community?

The description of “the long night of sleeplessness” suggests a community plagued by worry and grief. It portrays an enduring sense of anxiety and mourning, indicating that the traumas of conflict and loss have left deep psychological scars on those who remain.

10. Why does the poet choose to use free verse for this poem?

(The use of free verse in this poem allows the poet more flexibility to explore complex emotions and themes without the constraints of traditional poetic forms. This style mirrors the chaotic and tumultuous experiences described in the poem, enabling a more natural and expressive delivery of the speaker’s feelings and the community’s struggles.

Looking for something specific?

[ivory-search id="163692" title="Default Search Form"]

Leave a Comment